History: How the Wetsuit Became the Surfer's Second Skin

Share

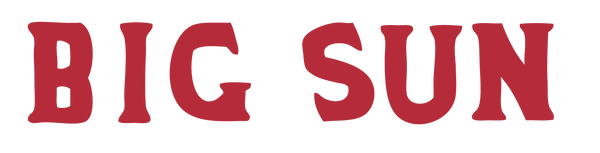

Above: Diver John Foster wears two of Bradner’s early neoprene wetsuit prototypes, circa 1952. Images courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives, UC San Diego Library.

When Bob Meistrell started surfing in Northern California during the early 1950s, 20 minutes was about all he could stand in the frigid coastal waters. Despite the constant rush of adrenaline, after three or four good waves, the late Body Glove co-founder was hightailing it back to a dry towel in the warmth of his car. With water temperatures near Santa Cruz hovering in the mid-50s, the surf was cold enough for a swimmer to catch hypothermia in an hour.

“He’d be surfing at Ocean Beach basically in rubber overalls filled with water.”

This unpleasant reality is in sharp contrast to popular depictions of early American surf-culture, which are all skimpy swimsuits and suntanned skin. Bands like the Beach Boys and films like Annette Funicello’s “Beach Blanket Bingo” cemented an image that revolved around the southern tip of California or the tepid waters of Hawaii. In fact, most beaches on the California coast were simply too cold for surfers to get their fix, inspiring pioneers like Meistrell to start tinkering with some creative solutions.

However, the first neoprene wetsuit wasn’t developed by a surfer, but by a Berkeley physicist named Hugh Bradner, whose contributions are sometimes overlooked. In 1951, Bradner was working in conjunction with researchers at University of California, Berkeley, and the U.S. Navy to design a diving suit for the military that didn’t need to prevent water intrusion to keep the wearer warm. Hence the name “wetsuit.”

Above: Body Glove’s first wetsuit size chart used this photographic diagram. Image courtesy of Body Glove.

A fellow researcher suggested Bradner try a foamed neoprene material made by a company called Rubatex. (At the time, extruded neoprene strips were primarily used as a sealant around gaskets for automobiles and airplanes.) Neoprene was filled with tiny, uniform air bubbles that helped insulate against the cold, even without being skintight. Divers working with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography tested Bradner’s early prototypes, and his best designs utilized the thick, foam-rubber material with fantastic results.

Apparently, Bradner preferred his wetsuit research to benefit the U.S. Navy rather than profiting from their production. In a letter dated December 8, 1952, Bradner wrote, “I plan to get someone started to making the foam suits commercially within the next month or two, if all goes well. I do not anticipate any particular difficulty, since I specifically wish to avoid any profit to myself. I don’t want to compromise my position of unbiased consultation on swimmers’ problems.”

Instead of pushing for his own patent, Bradner allowed the application to pass to the University of California, which abandoned the project after determining the market for watersport equipment was too limited; in 1952, there were relatively few surfers and divers around the world.

True to his word, Bradner formed the Engineering Development Company, or EDCO, with some colleagues in order to manufacture his “Sub-Mariner” suit. As quoted in an ad from Skin Diver magazine, a short version of the Sub-Mariner sold for $45, which would be approximately $400 today, while the full suit cost $75. Regardless of price, Bradner’s company couldn’t compete with brands developed by the actual athletes who used wetsuits, like surfer Jack O’Neill.

Above: Two divers wear frogmen-style drysuits, like those worn by O’Neill during his early surfing days. Image courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives, UC San Diego Library.

The same year that Bradner’s company got started, Jack O’Neill opened the first O’Neill surf shop in his garage near Ocean Beach in San Francisco. As an avid surfing and diving enthusiast, O’Neill had been testing various methods to keep warm while surfing off the Northern California coast. These included soaking sweaters in kerosene to make them more water resistant and experimenting with rubber drysuits worn by Navy frogmen, or underwater divers. The two-part frogmen outfits were tightly sealed at the wrists and ankles to prevent water from entering the suit, and worn over long underwear to stay warm.

“They’d roll the top and bottom together to seal around the waist,” explains Brian Kilpatrick, O’Neill’s Director of Marketing Communications. “You’d be good for half an hour before the seal would break and then the waders would fill up with water, and you’d be lucky to survive. You can imagine how dangerous that was: He’d be surfing at Ocean Beach basically in rubber overalls filled with water. Super scary.”

Though the drysuit let O’Neill stay in the water a bit longer, he realized it wasn’t a safe solution. Around the same time that Bradner was conducting his experiments in Berkeley, O’Neill got wind of neoprene from a pharmacist friend, who suggested it as an insulator. O’Neill applied a thin layer of PVC plastic sheeting to one side in order to strengthen the material, and then hand-cut neoprene panels to the desired size. Beginning with a swimsuit brief and vest, O’Neill constructed and tested his first wetsuit designs himself.

Then in 1956, O’Neill introduced the wetsuit to a wider audience: At a sporting goods trade show in San Francisco, he set up a full swimming pool, and had his kids float around in their full-length wetsuits along with surfboards, inflatable rafts, and big chunks of ice. The orders started rolling in.

Above: Jack O’Neill’s kids floated around in their custom wetsuits at a 1956 trade show in San Francisco.

Meanwhile, down in Redondo Beach, Bob Meistrell and his twin brother Bill had been experimenting with their own wetsuit designs. Having grown up in landlocked Missouri, the Meistrells were mesmerized by the ocean, and first attempted diving in a local pond using a vegetable-oil can as a helmet rigged up with a bike pump to deliver fresh oxygen. In 1944, at age 16, the Meistrell brothers moved to Manhattan Beach, and were finally able to explore the sea as they’d always wanted.

“The Dive N’ Surf crew would host contests to see which surfer could get in and out of their wetsuit the fastest.”

Fresh out of high school, the boys were drafted to join the Korean War effort in 1950, with Bill heading to South Korea and Bob to the Fort Ord base in Monterey, California. Many evenings, after getting off his shift, Bob would meet up with friends to surf at Pleasure Point near Santa Cruz. In the dim glow of his car headlights, Meistrell was happily engulfed by the frigid water, at one with the waves. “I surfed there for two years at night by car light,” explained Meistrell, who recently passed away. “And with just a sweater on, an army-issued wool sweater.” The thick wool kept Meistrell’s torso warm for a few good rides, but quickly soaked through and let in the cold.

After Bill returned from Korea, the brothers became two of the first certified SCUBA instructors in the state. But years after they’d fallen in love with the sea, they still couldn’t stay in the cold water as long as they wanted to. As luck would have it, their friend Bev Morgan had been introduced to Hugh Bradner while he was doing research at Scripps. Morgan created his own wetsuit prototype based on a design Bradner shared with him, and continued making them for surfer friends like the Meistrells.

In 1953, Morgan opened the original Redondo Beach Dive N’ Surf shop, and soon asked the Meistrells to become partners in the business and help produce his wetsuits. “We were just cutting them out by hand,” Meistrell said of the early Dive N’ Surf designs, “and we’d sew them up with a glue and then hitch them together with a clamp.”

But most surfers weren’t sold on the benefits of wetsuits, and many continued to brave the cold waters without one. Early designs often restricted mobility, and their rough rubber interiors irritated the skin. Additionally, the thick neoprene material and lack of zippers made them very difficult to put on, so much that the Dive N’ Surf crew would host contests to see which surfer could get in and out of their wetsuit the fastest.

“Wearing a diving wetsuit when the water was cold wasn’t such a foreign idea, but it just didn’t occur to us that this piece of diving gear would translate to surfing,” says Steve Pezman, a lifelong surfer who founded The Surfer’s Journal. “The dive suits were so gnarly that you’d get these really bad rashes under your arms from paddling. They just weren’t made for vigorous arm use. You could swim in them, but mostly diving is about kicking with your feet. Since the other end was propelling you while you were surfing, the design needed to improve at the top.”

Until that happened, the wetsuit had a bit of stigma attached to it. “For a while, they said only sissies would wear wetsuits,” Meistrell pointed out. Though not for long, as Bill began searching out a lighter, stretchier material, which took him back to the headquarters of Rubatex in Bedford, Virginia, to learn about their different rubber products and work with the company to produce the best possible wetsuit fabric.

The Meistrells adopted the term “thermocline” for their wetsuit branding, which describes a zone of air or water where the temperature changes quickly. But Duke Boyd, whom the brothers hired as a marketing consultant, felt that “Dive N’ Surf Thermocline Wetsuits” was an unwieldy name for hip, new surf gear. According to Bob Meistrell, Boyd asked them, “What makes your suits better than anyone else?” And the brothers replied, “They fit like a glove.” A few days later, Boyd returned to their shop with a finished version of their classic, circular hand logo labeled “The Body Glove.”

Above: By the 1960s, surfers were familiar with the wetsuit-clad Body Glove surf team.

The brothers went on to produce their wetsuits for anyone who needed them: Professional divers, military personnel, film actors, and even a few animals. “That’s how far production companies get carried away with their stories,” said Meistrell. “They were worried if Lassie went in the water and wasn’t able to swim that a wetsuit would help Lassie float. So we ended up making one, and it included a coating of fur on the top, so that he didn’t look any bigger when he got wet.”

Since those early days, both Body Glove and O’Neill have continued to improve their wetsuit designs, but the central concept has remained unchanged. By 1966, when the ultimate surf film, “The Endless Summer,” was released, watersports enthusiasts had a variety of suits to choose from, and no longer needed to trek across the globe to avoid colder waters. Surfing took off, in reality and the popular imagination, growing into a professional sport and international pastime.

“I don’t think Jack ever foresaw this becoming an industry, the surf industry,” reflects O’Neill’s publicist Kilpatrick. “When you talk about the industry, about him being a businessman and an entrepreneur or any of that stuff, he just laughs and says, ‘I’m a surfer.'” Last year, O’Neill Wetsuits celebrated its 60th anniversary, and Body Glove is currently doing the same.

“I remember being a little kid,” continues Kilpatrick, “and my first wetsuit was a beaver tail, just the jacket. Trying to make it through winter with just a jacket with no shorts was a nightmare.” Kilpatrick, who lives in Santa Cruz, says that he never surfs without a wetsuit today. “I can’t believe how far we’ve come. All these minor adjustments and improvements on material, durability, entries and exits, and even your knee pads, your wrist seals, all this fine-tuning of these minute details really improves the user experience and makes your session that much more fun.”

Not only did wetsuits improve the experience for seasoned surfers, but they made the sport more accessible for millions of people who might never have tried it. “When surfboards went from redwood planks to fiberglass and balsa forms in the 1940s, that was the first breakthrough,” explains Pezman, “because the surfboard became user-friendly, lighter, more durable, and more available. Then the next big deal was the wetsuit, because it allowed year-round surfing. Today, there’s no place that’s off limits due to water temperature. In the northeast, they surf in the snow. They surf in Iceland, they’ve surfed in Antarctica, so it’s probably quadrupled the coastline that’s eligible for waves, and some of the world’s best waves are on those colder coastlines. So it’s had a huge, profound effect on the sport of surfing.”

“The wetsuit changed watersports in a huge way,” agrees Bev Morgan, the original Dive N’ Surf founder. “A person could be comfortable in much colder water, so the season expanded to become year-round, for all watersports. The closed-cell chambers within the material also made the user buoyant, which also made watersports safer.”

Bob Meistrell also stresses the wetsuit’s life-saving capability, a benefit that goes far beyond the physical comfort they provide for divers and surfers. He’s heard countless stories of the lives they saved after someone was stranded or knocked unconscious while in deep water. “A life jacket will keep you afloat until they find your body,” said Meistrell, “but a wetsuit will keep you afloat until they find you alive.”

Above: Australian surfer Simon Anderson wearing a cropped wetsuit during the 1980s.

Written By Hunter Oatman-Stanford. Original Article Source: Collectors Weekly.